Yes, Chef, Yes: "The Bear" as it exists in my head

Hi, you have reached the voicemail of Richie Jerimovich, the Goddess of Agriculture.

This introduction will be brief.

Below is a collection of my thoughts on FX’s show “The Bear.” It’s long.

And by long, I mean long. I had a page full of topic ideas before I even had anything fleshed out. No notes or anything. A PAGE OF JUST IDEAS. I’ve condensed them greatly — sacrificed a section on how dreamy Jeremy Allen White is — and come up with this.

It’s not a comprehensive analysis by any means. It is also not nearly in-depth enough to cover the scope of my emotions towards this show. I’m a little bit pained to send this into the universe knowing it’s not all I have to say, but unless I want to write about “The Bear” for the next 6 years, this will have to suffice.

I am asking — nay, begging — you to talk to me about this show, though, so if you read this and feel strongly about “The Bear” and/or my judgement of it, I would love to hear from you! :)

Anyway, again, this isn’t everything, but it is still quite long. Sorry.

If you haven’t seen “The Bear,” you’re welcome to read still. Nothing I say will have any meaning to you, but I worked quite hard on this and thus would appreciate the validation. You know how it is. Spoiler alerts, though, obviously.

“Sexy and Sweaty Sensory Overload”

One of my favorite places in Gainesville is used bookstore chain 2nd and Charles. 2nd and Charles is owned by multimillion dollar company Books-A-Million, so there’s no kitschy charm like you’d imagine from a used bookstore.

2nd and Charles is just a weirdly corporate store that sells strange books people found in their garage and brought in for a quick buck. (I bought my copy of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides there, and had to wipe it down with a Clorox wipe when I got home because it had an unidentifiable goop on it. Strange, I’m telling you.)

But strangeness aside, 2nd and Charles is my favorite for one major reason — cheap books.

I used to go on bad days and let the poor organization of the store cradle me, running my fingers over cracked book spines and worn out covers.

On one of these 2nd and Charles trips, I stumbled across Stephanie Danler’s novel Sweetbitter. It was $6 and about New York City, so I was sold, naturally. I’m easy when it comes to picking books, I suppose.

It turns out Sweetbitter is less about New York City and more about this fancy restaurant — the staff dynamics and how they relate to the hospitality industry as a whole. It’s about sex, drugs, food service and wine. And it’s fucking awesome.

I had recently finished Sweetbitter when I started watching “The Bear.” There are obvious connections between the two in subject matter, primarily: restaurant antics.

Both have a new girl joining a tight-knit team of kitchen staff: Syd in “The Bear” mirrors Tess from Sweetbitter. Both have a closed-off older woman the new girl is trying to figure out: “The Bear” has Tina and Sweetbitter has Simone.

And of course — in the true fashion of the type of media I consume — both Sweetbitter and “The Bear” have a grungy wet-mop of a man characterized by his tattoos and unstable emotional state: Jake, meet Carmy.

But more than the setting and characters, I find the main connecting factor of the two works to be their composition.

A review on the back of Sweetbitter describes the book as “a sexy, sweaty book of sensory overload.” I meaaaan. What a lovely and perfect way to describe anything.

Sexy. Sweaty. Sensory overload. I want to live there.

Obvious to those who have seen it, “The Bear” could be described the same — a sexy, sweaty TV show of a lot of sensory overload.

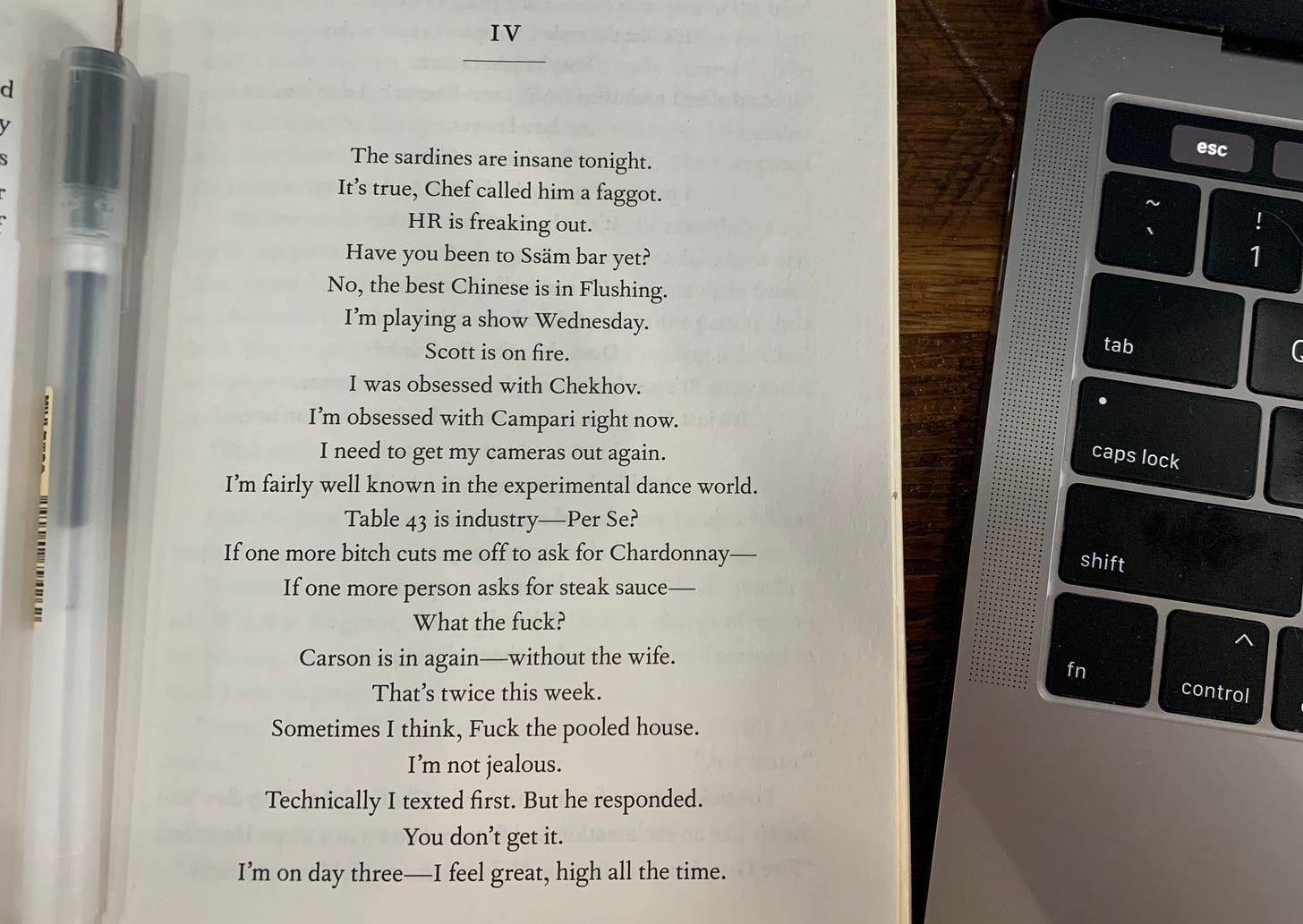

In Sweetbitter, there are these beautiful poetic sections that break up the novel.

Readers are taken out of protagonist Tess’ internal monologue to read a conversation between multiple members of her fellow kitchen staff.

These conversations are structured similar to poetry, line by line, with no real narrative structure. They don’t follow any true dialogue — the answer to a question proposed in line one could be found in line seven, and even then, you may have to use some higher-order thinking to connect the lines.

It’s chaotic and a bit confusing as a reader — and then you get it, that that’s how the kitchen feels. It works, and it’s wonderful.

The mind-scrambling effect Sweetbitter’s poetry creates is akin to the absolutely genius editing on “The Bear.”

The sensory-overloaded structure of the show is one of the first things that pulled me in. I’m sure most viewers would agree. It’s difficult to look away from that first episode for fear of missing some minute detail. It’s immediately, well, sexy and sweaty and overwhelming.

The first time viewers see Carmy and the restaurant, we see it through quick flashes of pay stubs and overdue bills and funeral programs.

There’s singing and sirens and yelling and video game beeping in the background — everything is frenetic and fast and hectic instantly.

Adding to that, the first time we hear real silence in the show is after Richie literally fires a gun into the air towards the end of the first episode.

But first episode aside, I would be remiss to talk about “sensory overload” in regards to “The Bear” without talking about episode seven.

Oh, episode seven, my beloved.

I tried to watch episode seven in the bath. A bath, for me, is a time to decompress — to light a candle and shut my brain off. Unfortunately, episode seven of “The Bear” is not conducive to this.

It’s one of the most stressful episodes of television I have seen in a long time. It’s one 20-minute long shot — no cuts.

In the beginning of the episode, we’re building up to the first time the restaurant begins taking to-go orders with a new system. It’s inherently anxiety-provoking, just the nature of anticipating a new system, especially one that we’re not convinced anyone in the kitchen really understands save for Syd and Carmy. There’s a lot of arguing happening, but nothing making my blood pressure spike.

But then there’s 10 minutes left in the episode and Richie predicts — or jinxes, maybe — the future, saying, “This is gonna be bad.”

Immediately after, we find out that Syd accidentally left the pre-order option open on the to-go tablet, and all hell breaks loose. “We have 255 beef sandwiches due up in 8 minutes,” Carmy says. Conveniently, there are 8 minutes left in the episode.

Shit goes crazy! Richie gets stabbed! Syd quits! Carmy kills a doughnut! But I’ll spare you any more play by play, because it makes my heart race to watch this episode and to relive it any more than I need to would probably call for upping my Zoloft dose.

I’ve never worked in a restaurant before, but from Sweetbitter’s cacophony of voices to “The Bear” episode seven, I’m lead to believe that this is sort of how it feels. Sensory overload.

In episode 8, following the to-go fiasco, Syd says, “It would be weird to work in a restaurant and not lose your mind.” In that case, I suppose I feel the same about working in a restaurant the same way I feel about using Snapchat: I respect those who can do it, but it all appears too overwhelming to me.

the bear is guy fleabag send tweet

The argument brought up in this tweet, that “The Bear” is “Fleabag” for men, is one that I am utterly enraptured with.

And I absolutely agree. I love this comparison.

If you haven’t seen Fleabag, it’s a must-see. I’ll be giving some minor descriptions of the show’s plot, characters and theme here, but nothing I’d mark as a spoiler per se. But if you’d prefer to go into watching it completely blindly, skip this section. :)

Fleabag, the character, has done terrible things. Personally, I don’t think Carmy’s sins hold a candle to Fleabag’s — she’s intentionally acting out, while Carmy is just hotheaded and closed-off. His negative moments are often just poor regulation of emotions rather than intentional unkind actions.

In this sense, I find the shows different. Carmy is aware of his flaws and takes steps to ensure his errors aren’t detrimental to his relationships with others. He apologizes to Syd and Marcus and his staff multiple times throughout the series; he attends Al-Anon meetings in an effort to salvage both his relationship with Sugar and his posthumous relationship with Michael. On the other hand, Fleabag sits in her wrongdoings, finding comfort in her negativity.

But despite the tiny differences in Fleabag and Carmy as characters, “Fleabag” and “The Bear” are markedly similar, especially in theme. Both shows are about grief and the complex ways it can affect relationships with yourself and others.

The grief Fleabag and Carmy carry serves as the pulse underneath their actions. It guides them, stuns them, agitates them, pushes them.

I feel like on paper, yes, viewers of these shows should understand that grief plays a big role in a character’s actions.

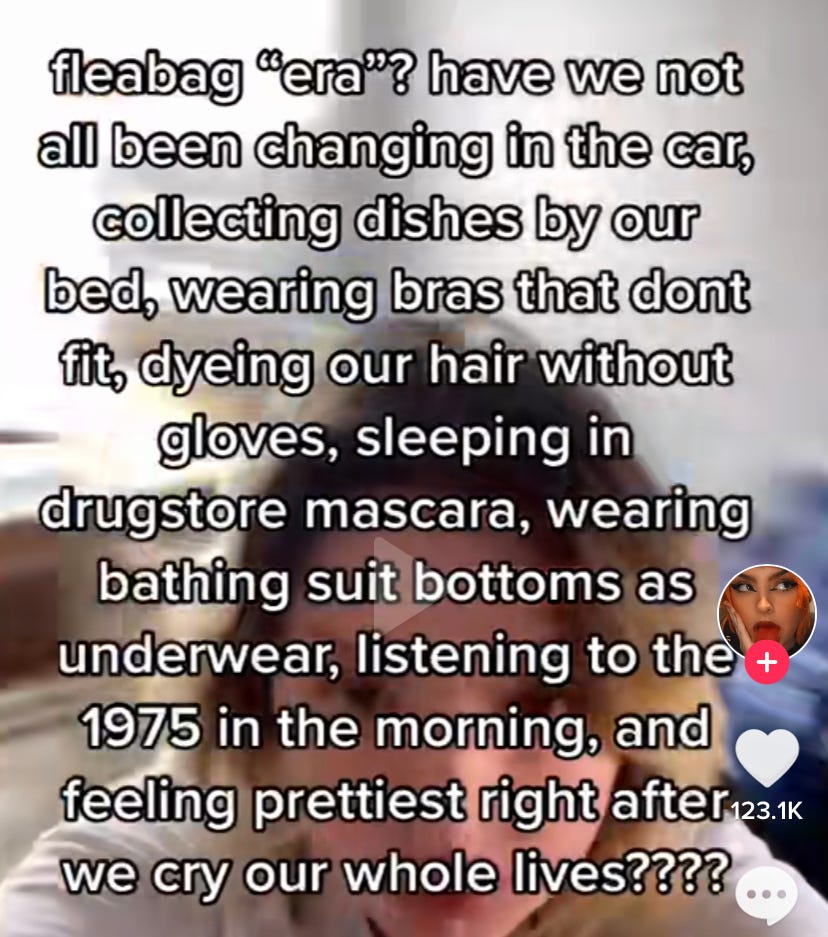

I feel like “Fleabag” in particular, though, gets misunderstood and reduced to a show serving “crazy, unhinged woman” agenda. This interpretation of the show doesn’t acknowledge the important and soul-crushing emotions Fleabag is feeling underneath her “collecting dishes by her bed” exterior.

The misunderstanding of characters experiencing a world-shattering grief by a media-literacy-lacking public is common.

In J.D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye, Holden Caulfield is a beautifully written character — a child struggling with the death of his brother — and yet his story is often misinterpreted to just a pompous, privileged, grating teenager flippantly experiencing the real world for the first time.

But Holden is a child. His brother passed away. The novel is about him learning to live with his grief and navigating mental health. The story is told through Holden’s insufferable snark and objectively bad points of view, yes, but that’s the point!

If you can’t read past the literal words of the book, Holden’s relaying of events, to connect the greater theme of what’s going on, that’s not Salinger’s fault. Holden is a narrator that you’re supposed to cringe at, but simultaneously feel for him as you see his thought-processes have been warped by circumstance.

The way “The Catcher in the Rye” is about Holden’s adventures in New York City is the way “The Bear” is about a Chicago beef restaurant. It’s not.

Carmy is an asshole—viewers literally read that on the screen in episode 8. He is unkind and brusque. But he’s also going through something huge and life-changing. Just like Holden, just like Fleabag.

It’s a disservice to the show to reduce Carmy to his sad-boy demeanor. That’s absolutely reductive to the broader themes of the show. I feel the same about Fleabag, clearly.

And it’s not that this is a particularly profound analysis by any means — I’m sure it’s pretty damn obvious that “The Bear” is about grief. I’m not claiming to be unlocking the secrets of the show here.

I just think that the most obvious evidence to prove that, yeah, “The Bear” is guy “Fleabag,” is the common misunderstanding of the main characters. They’ve both been reduced to be palatable by social media and memes, but are complex and well-written characters.

Maybe you’re rolling your eyes at me now; maybe I was meant to just look at that tweet and laugh.

But I’m so fascinated by the interpretation of sad and sometimes objectively unfavorable characters by the general public.

Where is the disconnect happening? Why?

Perhaps it’s a result of mass consumption — watching 8 episodes as quick as possible to be up-to-date on a show everyone’s talking about, or setting a high Goodreads goal and devouring novels quickly with little to no reading comprehension or recall.

Or maybe “The Bear” and “Fleabag” bring up emotions we aren’t equipped to deal with. We see ourselves in the characters’ despondence but can’t fathom that we could ever behave the way do.

Spoiler alert, we can and we do.

And because we act out just like Carmy does, I think it’s important that we make sure the themes of the show don’t get lost. It’ll bring you closer to yourself to examine the media you consume mindfully.

Girl Help, My Found Family is Experiencing Profound Grief

I love the found family trope. I mean, my favorite show is “New Girl.” There’s no denying that I’m a sucker for a group of people who on paper shouldn’t get along BUT, against the odds, find joy and love in their relationships with each other.

I eat it up every. single. time.

“The Bear’s” found family is way less overt than the “we literally live together” trope in “New Girl.” In fact, the only times we as viewers really get a “found family” moment are rare.

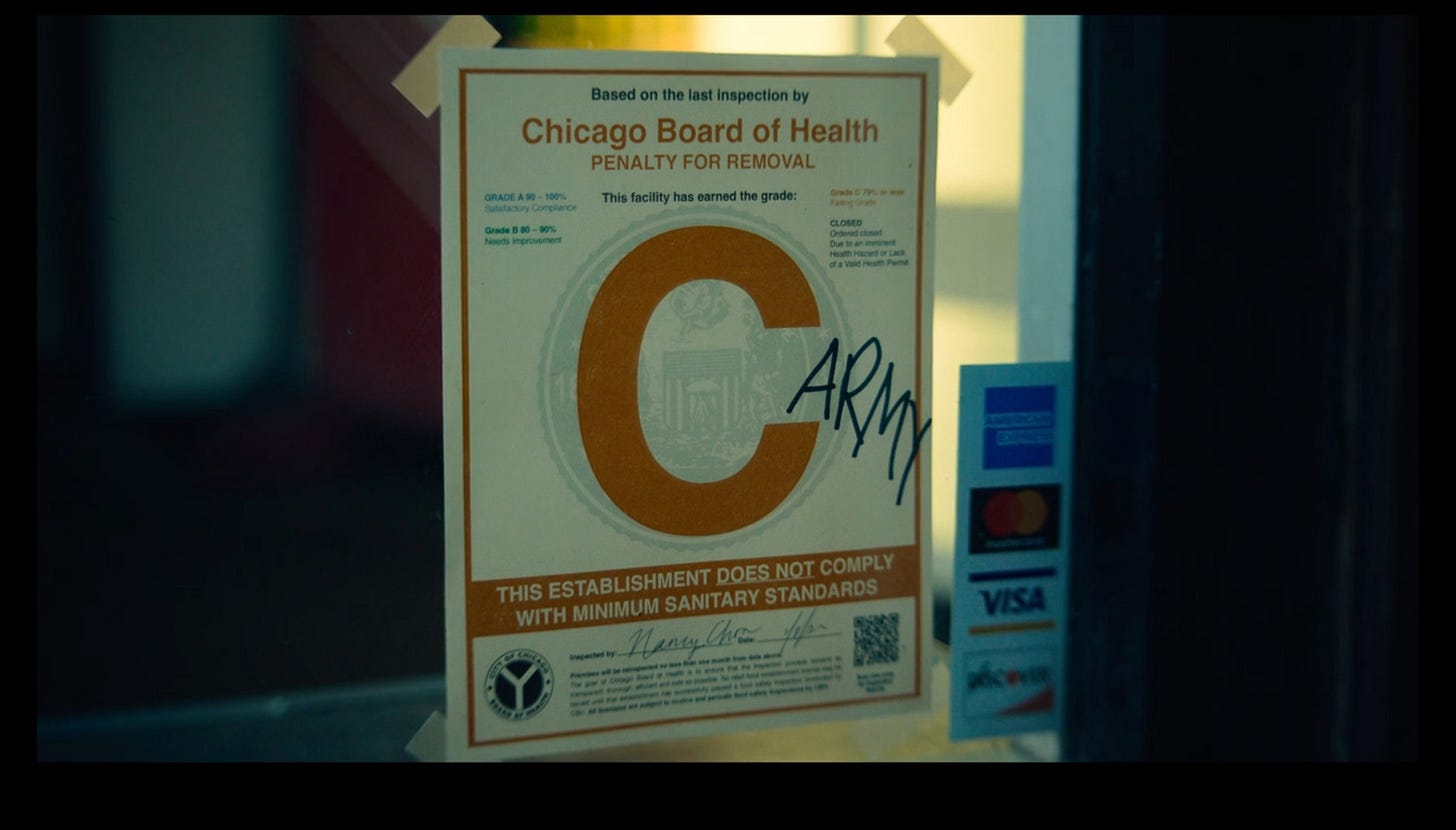

Often they’re hidden in the background, like the subtle jest that happens through written words, like the writing of Carmy’s name on the Health Inspector score sheet or the aforementioned “Carmy is an asshole” note. We never see these things being written, but their existence indicates a shared moment of laughter and gossip between characters. Viewers aren’t privy to those moments, much to my chagrin.

But they exist!

They exist simply as an indication that viewers are only getting a very small glimpse into the dynamic between these people. There’s history and complexities we don’t get to see unfold in real-time. Instead, they’re tucked into the details.

We do get to see a fair amount of a playfully argumentative dynamic unfold on screen, though.

My favorite is in episode one. The team is sitting, eating the family meal Sydney made and talking about what they’re grateful for. When it’s Marcus’ turn, he doesn’t opt to proclaim gratitude for the other people in the room, like Tina does (“I’m grateful for all y’all motherfuckers,” in true Tina style).

Instead, he says, “I’m grateful that Richie didn’t come in here wearing that cologne he always be wearing, you know, it smell like a pine tree and shit.”

Okay, I admit it doesn’t read as wonderfully as Lionel Boyce’s delivery of the line is. But in the context, it’s so funny and perfect. To me, it’s a great primer of the team’s relationship. They express gratitude for each other through teasing and argument.

We get this spelled out for us in episode 5, when, while hugging after an argument, Sugar asks Carmy, “Will you fight with me tomorrow?” :):

One of the plots we follow through the show is Sydney’s strife with other members of the staff — particularly Tina and Richie — as she comes in and serves as a vessel for all of Carmy’s changes. Syd is one of the most wonderfully written TV characters of recent entertainment and the nuances of how she navigates relationships with her new peers are often most indicative of the “found family” dynamic in the restaurant.

Tina and Syd butt heads throughout the entire season. In episode two, Tina confidently announces her disdain for Sydney with an insanely comical (and real?) line: ”Beware of bitches with little notebooks.”

We see them reconcile their differences at the end, though. The first indicator of this mutual ceasefire, mutual respect, is Tina calling Syd “chef” in episode 7.

In episode one, Carmy calls Tina “chef,” a term used as a sign of respect in the fancy French-style kitchens he worked at previously. Tina, not used to the term, is taken aback and mishears him as “Jeff.”

From that point, as the staff calling each other “chef” becomes more commonplace, Tina opts to use “Jeff” instead as an act of defiance against Carmy’s upper-echelon system changes — the “dumbass cult,” as she calls it in episode 3. (Tina has some great one-liners.)

But in episode 6, we see Tina shift. She tells Richie that the way the kitchen runs now is something good, that those changes Carmy made were working. And in episode 7, it happens: “Chef, you okay?” Tina asks Syd during the to-go system nightmare.

This episode is so quickly paced that viewers don’t get to sit in that for more than half a second. I sat in it for much, much longer. Syd is having a breakdown in this scene, her lowest point in terms of professionalism and poise, and yet this is the moment where we see Tina extend her olive branch of respect.

It’s so consistent with Tina’s characterization that it hurts — of course anti-change, anti-fancy Tina finally sees Syd when she breaks her resolve. It’s so sweet.

We learn in the show that Tina’s resistance to change — resistance to Syd — comes from a place of missing Michael. A poignant aspect of the found family in “The Bear” is that we as viewers know someone is missing. Michael is a key facet of the dynamic, despite only being physically shown in the show twice. One of those times is the closing shot of the season.

Everyone in that kitchen carries their love for Michael with them. All of the strife, and butting heads and resistance to change comes from a place of trying to keep Michael alive.

We see this with Tina’s resistance to Carmy and Syd’s changes, yes, but the most blatant manifestation of this love is Richie. We learn early in the season that despite him and Carmy calling each other “cousin,” they actually aren’t related. Michael was just Richie’s best friend.

I love knowing that Richie was close enough to Michael that he’s developed a familial bond with Michael’s family. Even Michael and Carmy’s uncle Cicero has a relationship with Richie, one definitely marked by the steeped-in-love arguments I discussed earlier.

It goes so far that Richie often forgets through the season that he isn’t actually Italian, as Carmy and Michael and Cicero are. This is one of my favorite running bits in the show, especially in episode 7, where Richie is absolutely bitching at Syd in Italian slang, and Syd and Carmy both remind him, harshly, that he is not even Italian.

But as the one closest to Michael, Richie is struggling in his death. He’s resistant to Carmy taking over the restaurant at first. Very resistant. Because this was Michael’s, right? How dare Carmy come in, a mere four months after Michael’s death, and change it all up?

Richie acts out in the restaurant because Carmy’s presence has fast-tracked Richie’s grief to a speed of healing that he wasn’t prepared to cope with. We see direct evidence of Richie avoiding healing when he doesn’t give Carmy the note from Michael right when he finds it.

Richie does come to terms with the change and the grief in the end. In a rare vulnerable moment in episode 8, he tells Carmy that Carmy is all he’s got. This scene feels like closure, like acceptance that Michael isn’t coming back. It feels like Richie understanding that he can carry love for Michael and still have room for growth.

In Michael’s death, each character has found themselves impossibly closer to those around them. They’re a found family that’s sharing something so special and painful. Despite the circumstances, Michael is still there with them. The love they have for him serves as its own entity.

I Made The Sandwich.

Watching “The Bear” is difficult for me, for I am an easily influenced person with a penchant for intense and all-consuming food cravings.

That means I can’t watch “The Bear” without needing an Italian beef sandwich.

So, hungry, I thought, what better way to both immerse myself in The Bear Cinematic Universe (TBCU) and satisfy my deep urge for The Sandwich than to make my own?

It was hardly a question.

After opting to go all in and make not only my own sandwich but my own giardiniera1, I ended up spending $117 on groceries. (To be fair, some of that money was spent on unrelated things, like Welch's fruit snacks.)

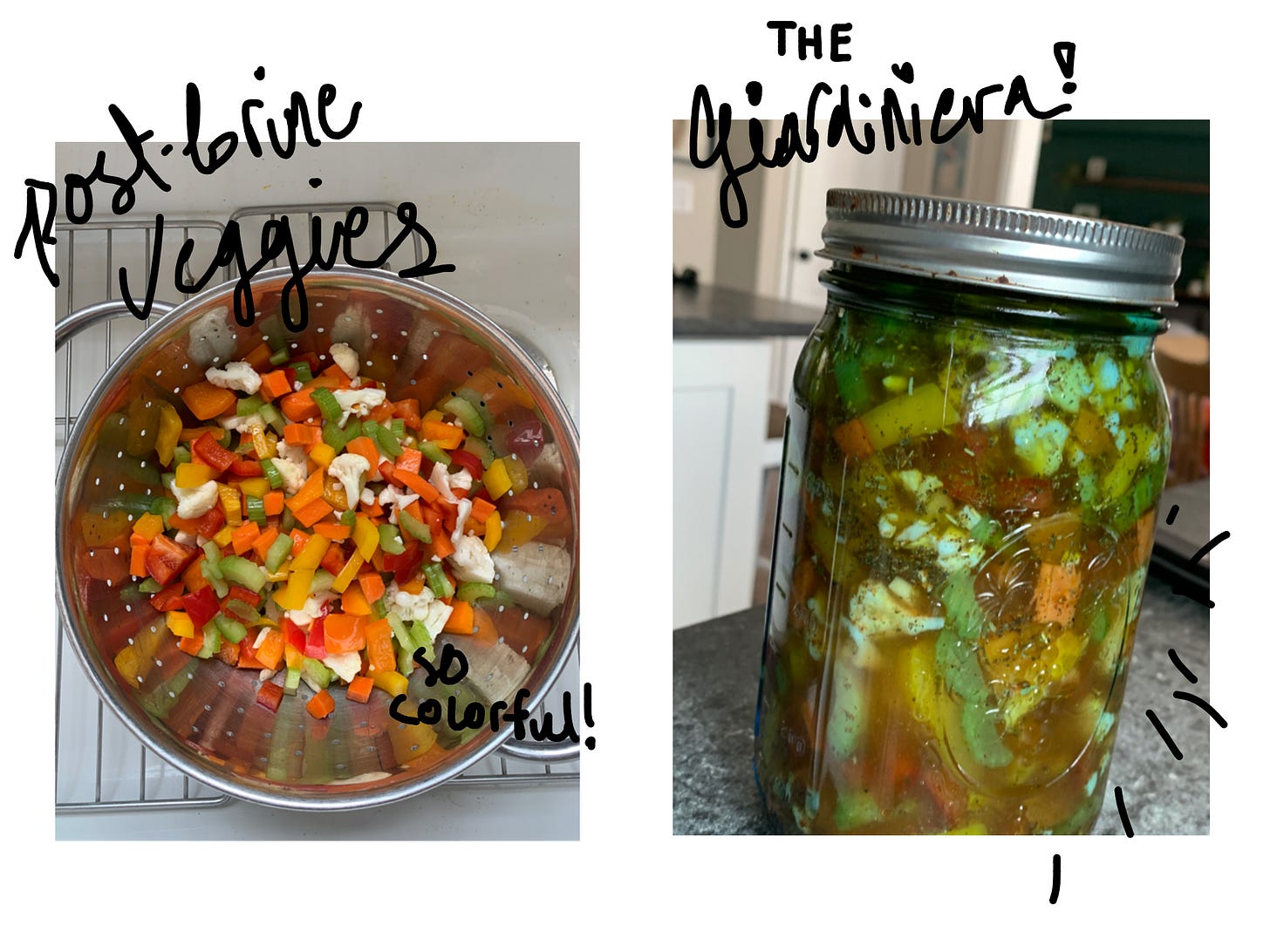

The giardiniera would be a three day long affair, so I quickly got to work. As soon as my grocery bags were emptied, I began chopping up the vegetables to get them ready for a nice 12+ hour brine. I learned almost immediately that Carmen Berzatto would chew me up and spit me out: I am astronomically slow at chopping vegetables, apparently.

Also, my mother is staunchly against spicy foods, so I was leaving out the best damn part of the giardiniera—the serrano peppers. :( :(

I was absolutely bastardizing the sandwich, and I hadn’t even gotten to the sandwich part yet.

But the giardiniera had to sit for a few days, which allowed me time to cool off and regroup before tackling The Beef.

On the day I was serving the sandwiches, I woke up early to get the beef into my slow-cooker, which, according to the Internet, is the easiest way to cook it. I seared it in a cast iron pan before adding it to the CrockPot with—you don’t really care about the recipe, do you? All that you need to know is that it smelt very good and took 7 or so hours to cook.

When it was time to eat, I put together some beautiful sandwiches with my giardiniera, pepperoncinis, roasted red peppers, a melty and smoky provolone, and the tender shredded beef. Whatever “bastardization" I had anticipated with my slow vegetable chopping was out of the window. Shit was incredible.

That damn giardiniera was the star of the show. I’ll make jars of that for as long as I live. I had it today on a salad and it was great. I could probably put it on a vanilla cupcake and still enjoy it.

In the kitchen, words of affirmation look different to me. In other contexts, I like to be verbally valued for my contributions. When I hear “good job, Hayley,” I soak it in like it’s sun.

But when cooking, the best “words” of affirmation are the lack thereof—the silence that comes from a ravenous bunch enjoying my food for the first time. In my family, silence is an indicator that the food is too good to stop eating—even for a second—to speak. It’s quiet while we indulge in the flavors, savor our first bites. I relish in that silence; it means I’ve stunned a usually obnoxiously loud bunch into quiet just with some seasonings.

Then we can get to complimenting me.

And they did, that sweet family of mine. Made a big show of acknowledging how I worked so hard and for so many days for a meal that was so good. I preened, of course.

Words of affirmation is my love language, sure, whatever, but on top of that, I think the food serves as a love language all of its own.

“The Bear” is a manifestation of that love language on screen.

In the last episode, we find out that Michael’s final goodbye to Carmy is an index card of his spaghetti recipe. Sure, the recipe leads the kitchen to money, too, but the recipe is the last thing Carmy has of Michael’s that he gets to keep. Gets to look at and hold and run his finger over the ink.

In episode one, Carmy firmly refuses to make the spaghetti, saying it makes no sense on the menu and is therefore “done. The end.”

But in the last episode, after the discovery of the recipe (and subsequent money), we see the kitchen staff enjoying the pasta together.

The spaghetti, then, isn’t only Michael’s love letter to Carmy, but his love letter to the entire team. Moreover, Carmy’s willingness to cook the meal after the 8 episode run of not wanting to, is his “I love you” to the staff.

We see, then, a final connection between Carmy and Michael: they both love the restaurant, and the restaurant loves them both back. This connection isn’t forged through the spaghetti, but it is certainly emphasized by it.

(It’s also worth noting that originally the spaghetti is served as a menu item at The Beef, but when we see it appear in the final episode, it’s only being served for Family meal. It’s something more tender now, something only the staff shares. Does that make you want to cry, too? Or am I just a mess?)

The use of food as a vessel for grieving Michael’s death is the motif throughout the season—quite obviously, too; the entire plot of the show is Carmy taking over a restaurant in the death of his brother. The spaghetti here is the culmination of the motif—the moment where we go, “Oh,” and finally get it.

I have 1.) a tendency to ramble and 2.) a tendency to find a lot of love in strange places, so I don’t want to get trapped in getting existential over a beef sandwich. Instead I'll just leave you with some food for thought.2

The idea to make those sandwiches was entirely selfish—I was craving them.

There’s something to be said, though, that there was never a doubt in my mind that I’d be sharing them with my family. There was never a doubt that the days of work I put in for the meal wasn’t an act of service, an act of love for them.

I omitted the serrano peppers, for god’s sake.

Maybe next I’ll make some spaghetti. :)

Because I normally don’t write in this format, I don’t usually get a chance to thank my lovely beta reader, but a “conclusion” section lends itself perfectly to it: Sophia, you are the most wonderful friend I have had the opportunity to know and love. Thank you for always reading first.

On giardiniera: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giardiniera